Michael Grimes has been called “Wall Street’s Silicon Valley whisperer” for landing a seemingly endless string of coveted deals for his bank, Morgan Stanley. In more recent years, it has served as the lead underwriter for Facebook, Uber, Spotify and Slack. Grimes, who has been a banker for 32 years — 25 of them at Morgan Stanley — has also played a role in the IPOs of Google, Salesforce, LinkedIn, Workday and hundreds of other companies.

Because some of these offerings have gone better than others, Morgan Stanley and other investment banks are now being asked by buzzy startups and their investors to embrace more direct listings, a maneuver pioneered by Spotify and copied by Slack wherein rather than sell a percentage of shares to the public in a fundraising event, companies are essentially moving all their stock from the private markets to public ones in one fell swoop.

They cost the companies less money in banking fees. They also immediately free everyone on a company’s cap table to share their shares if they so choose, which has made the concept especially popular with VCs like BIll Gurley and Michael Moritz — though investors also cite the money that companies have been leaving on the table with traditional IPOs. Gurley specifically has talked publicly about underpriced offerings costing newly public outfits $170 billion over the last 30 years.

Grimes, in a rare public appearance last week at a StrictlyVC event, said he supports direct listings completely, calling the “pricing mechanism” more efficient, “absolutely.” He has reason to be a proponent of this new “product.” Both Spotify and Slack turned to Morgan Stanley to organize their direct listings — a process that involves running simultaneous auctions to determine the price at which demand and supply meet — and to ensure there would be enough liquidity for the listings to go smoothly.

Given the success of both, the bank is now better positioned than any to continue orchestrating direct listings for potential issuers, including, reportedly, Airbnb and DoorDash. (Grimes wouldn’t confirm the plans of any companies with which Morgan Stanley plans to work.)

Still, during last week’s sit-down, we wanted to know more about how they work and whether there’s a chance that banks will eventually try to thwart the process, given that they require just as much work, are potentially less lucrative, and keep banks from rewarding some of their best customers — meaning the institutions that are accustomed to being funneled IPO shares ahead of retail investors in traditional offerings.

Grimes patiently sat through roughly 40 minutes of questions, all of which you can read tomorrow if you’re a subscriber of Extra Crunch, where much more of the transcript is being published. In the meantime, here are some highlights from our conversation:

Morgan Stanley was the lead underwriter for Uber. You don’t think Uber went public too late? It seems like it was enjoying a lot of momentum last year, so much so that it was reportedly told by bankers that it could be valued at $120 billion in an IPO — which is nearly triple where it’s valued right now. Did you think it would go out at that number?

MG: If you look at how companies are valued, at any given point of time right now, public companies with growth prospects and margins that are not yet at their mature margin, I think you’ll find on average price targets by either analysts who work at banks or buy-side investors that can be 100%, 200%, and 300% different from low to high. That’s a typical spread. You can have somebody believe a company will be worth $30, $60 or $80 per share three years out. That’s a huge amount of variability.

So that variability isn’t based on different timelines?

MG: It’s based on penetration. Let’s say, what, 100 million people or so [worldwide] have have been monthly active users of Uber, somewhere in that range. So what percentage of the population is that? Less than 1% or something. Is that 1% going to be 2%, 3%, 6%, 10%, 20%? Half a percent, because people stop using it and turn instead to some flying [taxi]?

So if you take all those variable, possible outcomes, you get huge variability in outcome. So it’s easy to say that everything should trade the same every day, but [look at what happened with Google]. You have some people saying maybe that is an an outcome that can happen here for companies, or maybe it won’t. Maybe they’ll [hit their] saturation [point] or face new competitors.

It’s really easy to be a pundit and say, ‘It should be higher’ or ‘It should be lower,’ but investors are making decisions about that every day.

Is it your job to be as optimistic as possible about the pricing? How are you coming up with the number, given all these variables?

MG: We think our job is to be realistically optimistic. If tech stops changing everything and software stops eating the world, there probably would be less of an optimistic bias. But fundamentally — it sounds obvious but sometimes people forget — you can only lose 100 percent of your money, and you can make multiples of your money. I don’t think VCs are as risk-averse as they say, by the way. Some 80% or 90% of investments end up under water, and 5% or 10% produce 10 or 20 or 30x and so that’s the portfolio approach. It’s not as pronounced with institutional investors investing at IPOs, but it’s the same concept: you can only lose 100 percent of your money.

Let’s say you put five equal quantums of investment out to work in five different companies and one of them grows tenfold. Do I even need to tell you what happened with the other four to know you made money? Worst case, you’ve more than doubled your money, and therefore you’re probably going to lean into that again. So generally speaking, there’s an upward bias, but our job is to be realistic and to try to get that right. We view it as a sacred obligation. There’s variability and volatility within that. We try to give really good advice on receptivity. And when the process works as intended, we have predicted it as well as you can within a range of high variability.

This summer on CNBC, Bill Gurley told viewers that banks, including the top banks, have mispriced IPOs to the tune of $170 billion over the last three years, meaning that’s the amount of money that companies left on the table. Do you think we need direct listings and can you explain why they could potentially be better?

MG: Sure. We think Bill has done a great service by focusing a spotlight on the product, which we innovated with Spotify and then later with Slack. We do love the product, we’re bullish on it.

You’re asking how they work?

TC: Yes, as it relates to price discovery. So in a direct offering, you’re talking to people who own the stock and people who might want to buy the stock to figure out where they meet, which doesn’t sound that different than what goes on with a traditional IPO.

MG: It’s actually different in a technical way. In a traditional IPO, there’s a range, let’s say $8 to $10. And the orders we’re taking every day for two weeks, let’s say, while the prospectus is filed, we’re taking orders from institutions [regarding] how many shares they want to buy within that range. That means generally within that range, they’re buying. It’s not binding but generally speaking, they’re going to follow through. If it’s outside of that range, we have to go back and ask them again. So if there’s a whole lot of demand and the number of shares being sold is fixed so that supply is fixed . . . the company’s goal is for oversubscription because they want an upward bias. They don’t want to trade up too much [and leave] money on the table and they don’t want to trade down at all — even a little bit — and they don’t want to trade flat because that could be [perceived] to be down; they want to trade up modestly. An exception was the Google IPO, which was designed to trade flat and traded up modestly, 14% or something like that.

The range might be moved once, maybe twice — because there’s not a lot of time because there’s a regulatory review to turn it around — so [let’s say] it’s moved from $8 to 10 to $10 to $12 and there’s still much more demand than supply; it’s a judgment call as to, is that going to price at $14? $15? $12? Some investors might think it should trade at $25 while others think it should trade at $12. So there could be real variability there, and when trading opens, only the shares that were sold the night before in the IPO, some subset of them are trading and that’s it, everything else is locked up — the whole cap table. So for six months, it’s those same shares trading over and over, other than maybe [a small sampling] or investors of former employees who weren’t locked up.

TC: Okay, so let’s switch now to a direct listing.

MG: So with a direct listing, the company is not issuing any shares. There is no underwriting where the banks buy the shares and sell them immediately to institutional and retail investors. But there is market making and the way the trading opens is similar but the size is totally flexible. There’s no lock-up. The whole cap table can essentially sell shares, versus the average IPO right now where I think it’s 16 percent of the cap table is sold in an IPO, and that’s down by half, by the way, from 15 years ago.

TC: So everyone can sell on day one, but are there handshake deals to ensure that not everyone dumps the shares on day one?

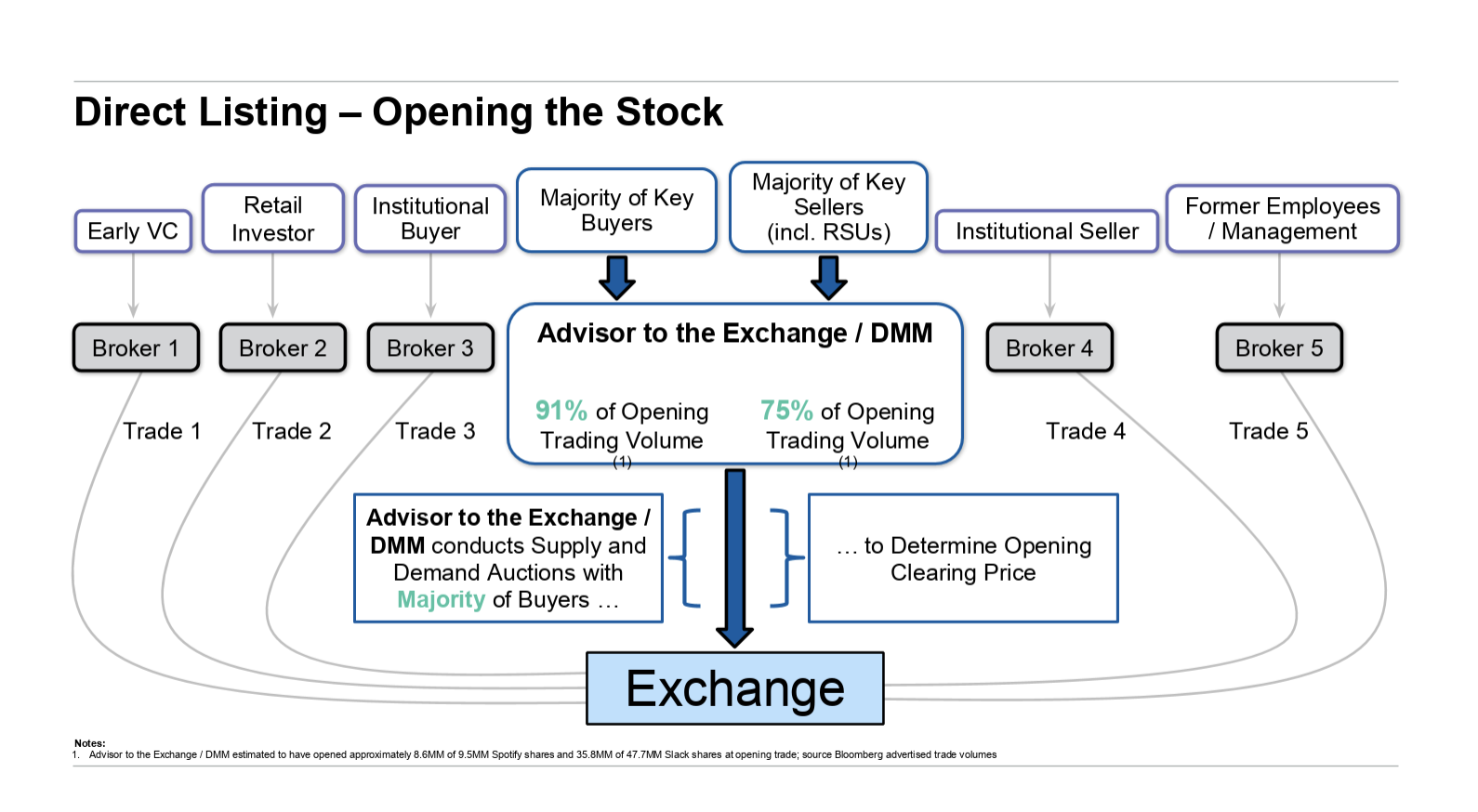

MG: No, there’s no hidden agreement. They can sell as many shares as they want, but it’s going to depend on the price. The way a direct listing opens trading is a critical function because there’s no order book. No one has been taking orders for two weeks. The company has met with investors and done investor education. We’ve helped them write a prospectus, etcetera, but there are no orders, there’s no price range, and off we go. With Slack and Spotify, we were the bank responsible for the trading. What that means is on our trading floor in Times Square, our head trader, John Paci, and his team are in touch with anyone on the cap table who might want to sell and institutional investors who might want to buy, and what’s happening are two auctions at the same time.

So in the traditional IPO, we were taking orders for size within a range that might move a little bit, [but] this is now any price. So take the buyers. [We’re trying to find out] who will pay $8 who will pay $12. Will anyone pay $16? So you’re taking that demand and sorting it by price. At the same time, you’re taking that supply, asking, ‘VC No. 1, is there a price at which you would sell shares?’ If this person says, ‘Yes, but at $20’ and we don’t have any demand at that price, then we figure out: who would sell at $18? Maybe VC No. 2 says they would sell 5 percent of their shares at $18. So we have some buyers, but it’s not enough to open trading with enough liquidity, which is key to all this. If you had one VC and one buyer, the buyer would go away. They’d say, ‘You didn’t tell me I was going to be trading with myself.’ So we have to figure out where a simultaneous demand auction for the highest price, and a supply reverse auction for the lowest price clears and meets. If you can move a billion dollars worth of stock at $14 and get demand for a billion worth of stock, then that’s the price.

That’s then sent to the exchange where the exchange can take and add any other market maker or bank that has another seller or a buyer — so they add in, call it, another 30 percent from other brokers — and that produces the opening transaction.

Stay tuned tomorrow for much more from that interview, where other discussion areas included whether lock-up periods might eventually be done away with in traditional IPOs, why VCs are suddenly so motivated to bang the drum on direct listings, and what really went wrong with Google’s auction-style offering back in 2004.