In Hefei, a Chinese city known for its relics from the Three Kingdoms period and its manufacturing industry today, Maxim Rate was thrilled to find a small studio crafting a Western role-playing game, a genre that attracts lovers of gritty aesthetics and dark storylines.

“The design and computer graphics are really good. You can’t tell they are a Chinese team,” said Rate.

Rate’s mission is to find Chinese studios like the bootstrapped Hefei team and help them woo international players. As Chinese regulators tighten rules on game publishing and make licenses hard to obtain in recent years, small studios find themselves struggling. Since last year, Apple has pulled thousands of unlicensed games from its Chinese App Store at the behest of local authorities. Small-time developers begin to look beyond their home turf.

“The problem is these startups have no experience in overseas expansion,” said Rate.

An avid gamer himself, Rate quit his job at a Chinese cross-border payment firm last year and launched a part-incubator, part-investment vehicle to take Chinese games abroad. The firm, called Westward Gaming Ventures, took inspiration from Zheng He, a Chinese diplomat and explorer who embarked on state-sponsored naval expeditions to the “Western Oceans” during the Ming Dynasty.

Westward plans to raise 200 million yuan ($30 million) for its debut fund, Rate told TechCrunch in an interview. It plans to deploy the capital over the next three years with an intended check size of 2-4 million yuan per studio. It’s currently in talks with 20-30 teams that span a wide range of genres.

The Chinese fund being established is a so-called Qualified Foreign Limited Partners Fund, which, for the first time, will enable foreign investors (USD and EUR) to invest directly in Chinese gaming firms. Only a few institutions own a license for QFLP, and while Westward itself doesn’t hold one, it gains legitimacy for direct foreign investment by partnering with the private equity arm of a major Chinese financial conglomerate, which declined to be named at this stage.

To navigate such regulatory complications, Westward also seeks help from its advisors, including one that oversaw the legal and financial process of one of the largest joint ventures established between Chinese and foreign gaming firms in recent years. The partnership, which can’t be named, was also the first time a foreign entity has become the majority shareholder in a gaming joint venture in China.

China limits foreign investments in areas it considers sensitive, such as value-added services, so many companies resort to setting up elaborate offshore entities to receive overseas funding. The restriction makes it difficult for resource-strapped studios to land foreign investors, who could help them venture into global markets. They are left with the option of getting backed or bought by Chinese giants like Tencent or ByteDance.

Rise of Chinese plays

The idea of Westward is not just to lower the barriers for independent Chinese games to secure foreign capital but also better prepare them for overseas expansion.

“Chinese gaming studios, big or small, used to rely heavily on ads for user acquisition when they went abroad,” said Rate. “Sometimes a game would take off, but the team had no idea why, so they continued to test. Those who failed may just give up.”

But taking a game abroad is not as simple as translating it, hitting the publish button and launching an ad campaign on Facebook.

Westward’s plan is to get involved in a game’s early development phase and help them position: Is it an RPG? Is the targeted user a casual or serious player? What’s the graphic style? In addition, the firm also plans to supply developers with workspace, technical assistance, marketing and localization expertise, connection to publishers, and overseas operation help.

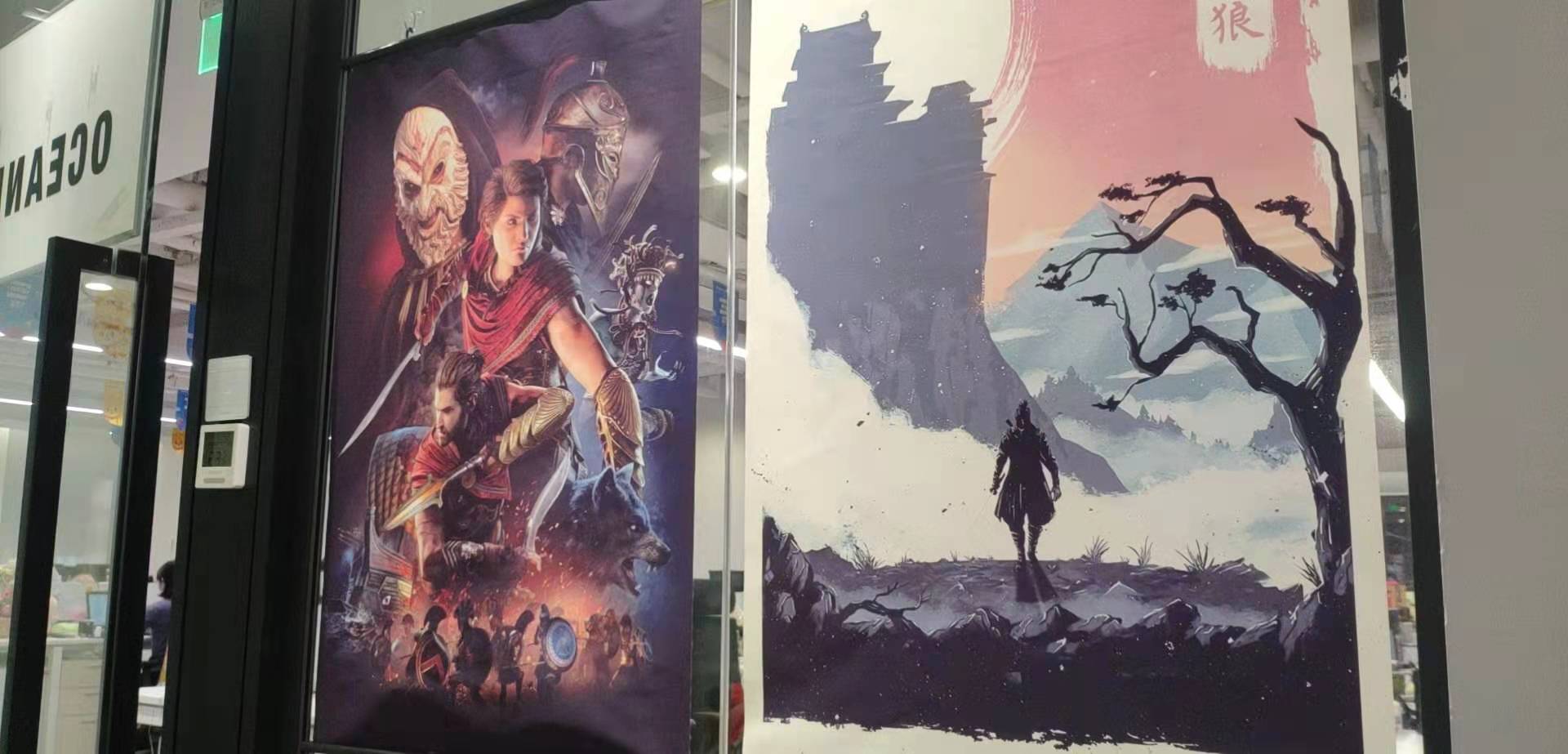

Image Credits: Westward Gaming Ventures

To provide post-investment support, Westward has partnered up with V+ Gaming Society, an incubator for games headquartered Shenzhen, which Westward also calls home.

Chinese tech companies are facing mounting challenges in the West as geopolitical tensions rise. Many now prefer calling themselves “global firms” and even deny their Chinese roots outright.

But for Westward, the games it helps doesn’t need to pretend they are non-Chinese. “Most players don’t consider where a game is from if it is a really good game,” said Rate.

“We actually hope to see elements of Chinese culture in these games that can be understood by overseas players.”

Amy Ho, a partner at Westward along with Rate and Edward He, said one of the few Chinese games that have managed to be both “Chinese” and transcend cultural boundaries is Chinese Parents. The simulation game became a global hit by letting users experience what it is like to raise a child in China.

The benchmark Rate gave was the generation of Japanese games that began exporting 20-30 years ago, which he described as “Japanese” in spirit but “globalized” in graphics and game design.

There have already been globally successful titles from Chinese makers like Tencent and rising studios Lilith and Mihoyo. In the past, many Chinese users on Steam would be asking foreign titles to rush out Chinese versions. Now, it’s not uncommon to see Western users demanding English editions of Chinese games, Rate observed.

Rather than politics, the bigger challenge, especially for small studios, is how to “collect key data for product iteration while complying with local privacy laws,” said Ho.

50-70% of Westward’s capital will come from Chinese institutions. The presence of Chinese investments inevitably leads to questions around censorship. Ho said while Westward provides resources and capital to studios, it will work to ensure their independence from investor influence.

If things go well, Westward could help facilitate cultural exchange between China and the rest of the world. Beijing has been trying to export the country’s soft power, and games may be a suitable conduit, suggested Rate. Amid the ongoing trade war, having foreign fundings in Chinese companies may also do good to China’s “brand”, he said.